In 2007 I was reading Internal Combustion: How Corporations and Governments Addicted the World to Oil and Derailed the Alternatives by Edwin Black (NY: St Martin's Press, 2006 ISBN-13: 978-0-312-35907-2) after seeing Black on CSPAN.

One of the informative stories he tells is of the partnership between Thomas Edison and Henry Ford to build an electric vehicle system together before WWI.

(136) In the fall of 1912, the promise of Edison's new battery rose to the next level. His latest wizardry would allow every home, automobile, and industrial source to function as a freestanding generating station.

In mid-September 1912, Edison announced the result of some fifty thousand experiments conducted during seven painstaking years - a radical new energy-self-sufficient home. He called it the Twentieth Century Suburban Residence. ostentatiously overstuffed with every modern gadget and appliance from a coffee percolator to a washing machine, to room heaters and coolers, to phonographs and tiny movie projectors - the mansion was an electric marvel. Every device and system, basement to roof, was powered by batteries replenished continuously by a small-scale household electrical generator.

(128) In May 1901, Edison formed the Edison Storage Battery Company and in August 1903 began churning out the cells composed of nine iron and nickel plates. Twenty such cells were packed under a Baker run-about and other vehicles and road tested for as many as five thousand rough and bumpy miles to demonstrate durability. Edison's batteries could be recharged in about three and a half hours, or about half the overnight duration required for lead competitors. Most exciting, he planned a handy supportive infrastructure to recharge the batteries. He wanted to create a widespread recharging network at trolley lines and central electrical stations, with such a network extending into the countryside. Where such facilities did not exist, he suggested erecting small windmills attached to electrical generators that would light the home at night and recharge the batteries while occupants slept, thereby creating energy independence for the average home and vehicle. Windmills or electrical siphoning from other facilities, he said, would be cheaper than the growing reliance on gasoline.

(137) The system's secret was an array of three simple tanks: one for water, a second for oil, and a third for gasoline - all connected to an on-site mini-generator itself regulated by an automatic voltage adjuster and a series of circuit breakers. The resident was to "start his engine and forget it" for days at a time. The system worked this way: Edison's Type A nickel-iron batteries would run the house and all its gizmos. Every two to three days, the batteries would become discharged. The system would detect the drained batteries. When cued by the system, the on-site generator would automatically replenish the nickel-iron batteries in a seven-hour recharging session, often even as the homeowner slept. A staged and redundant array of batteries ensured that energy levels throughout the abode remained constant even as some units were being recharged. The same generator would recharge the new Type A-powered vehicle soon to be mass-produced by Ford, thus completing the circle of individual energy independence.

The first fully operational house was Edison's grand mansion at Llewelyn Park, New Jersey. For its coverage, the New York Times photographed the home inside and out, toured all the rooms, and verified demonstrations of endless electrically driven devices, from toothbrush sanitizers to foot warmers. The pocket generating plant was a narrow and compact machine, designed to be situated either in the yard, in a shed, or in the basement. Its cost: as little as $500, although it came in larger and more expensive sizes capable of supplying greater-scale housing. Edison's Twentieth Century Suburban Residence would provide cheap, independent power to any suburban abode with a lot or the needed building space as well as the rural home beyond the lines of city power plants. Self-sufficiency was no longer a vision for tomorrow, but a reality.

Initially, the generators would operate off a small tank of gasoline that periodically needed to be refilled. Clearly, this temporarily retained the tether to petroleum. But plans were to switch from dependence on a modicum of weekly gasoline to small residential windmills - that is, as soon as one could be perfected.

Perhaps if they had continued their work, Edison and Ford would have come up with something like the windmills Marcellus Jacobs made in the 1920s and 1930s. I wonder if Buster Keaton's "Electric House" silent comedy was based upon Edison's vision.

This wasn't even the first attempt at thinking through an electric vehicle infrastructure. Originally, it was electric cars and trucks which seemed to be the winning ticket in the automotive race.

Salom and Morris and their Electric Carriage and Wagon Company had a 14 cab taxi fleet garaged on 39th St in NYC by 1897 and

(67) ....worked to laminate economies of scale and sense to good electromotive mechanics. A central garage crew of only six, and that included a washer, was all the staff needed to keep the dozen or so cabs humming seven days each week. Using specially constructed garage cranes, slightly elevated auto rails, and removable vehicle trays, batteries could be swapped out by a single mechanic in just seventy-five seconds. Spent batteries were then mechanically shuttled to the recharging room for the overnight refresh. Cruising at speeds of 10 to 20 mph, each taxicab covered some eleven city miles per day. In constant use, the small fleet transported approximately a thousand passengers monthly over a rough average of about one thousand miles per week. Accidents and mishaps occurred only once every 360 miles, but this number diminished as drivers gained more experience with the new machines.

By 1899 some major manufacturers were designing the delivery infrastructure with electrical recharging stations, electrical hydrants to be installed on the streets like fire hydrants.

(74) General Electric produced a commercial version, dubbed the Electrant, to cheaply dispense charges of 2.5 kilowatt hours of electricity for a mere twenty-five cents. Resembling a parking meter, a chest-high box contained wires and a connection to the same electrical grid that powered the rest of the city. GE was merely waiting to install them in every city.

In my storeroom, I have a copy of the poster which was a winning entry in a nation-wide contest to envison the electric vehicle future. I think it was sponsored by GM. It showed Cambridge, MA in 2008 with electrical vehicles everywhere and charging bollards, Electrants, on the streets. That contest was in the early 1990s. I thought they did a great job, which is why I asked for a copy of their poster presentation. Little did I know that it was at least the third time these plans had been drawn up.

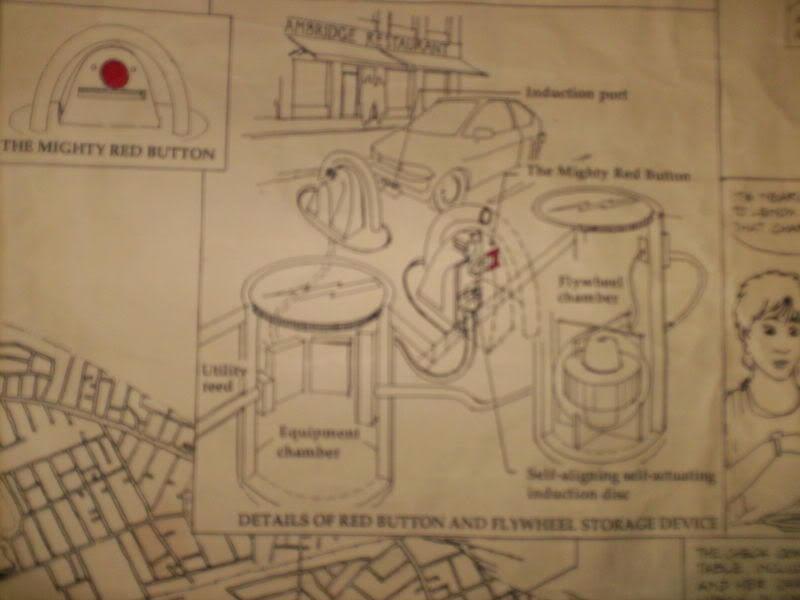

Here's their version of a charging station for electric vehicles:

Earlier entries in the Old Solar series:

Old Solar: Eames Solar Do-Nothing Machine

https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2009/4/15/719787/-Old-Solar:-Eames-Solar-Do-Nothing-Machine

Old Solar: Keck and Keck Twentieth Century Modern

https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2007/7/9/355768/-

Old Solar: 1881

http://solarray.blogspot.com/2010/02/old-solar-1881.html

Old Solar: Venetian Vernacular

https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2007/6/9/344834/-

Old Solar: 1980 Barnraised Solar Air Heater

https://solarray.blogspot.com/2008/09/old-solar-1980-barnraised-solar-air.html

Old Solar: JImmy Carter’s Green Deal

https://solarray.blogspot.com/2019/07/old-solar-jimmy-carters-1979-green-deal.html

Originally published February7, 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment